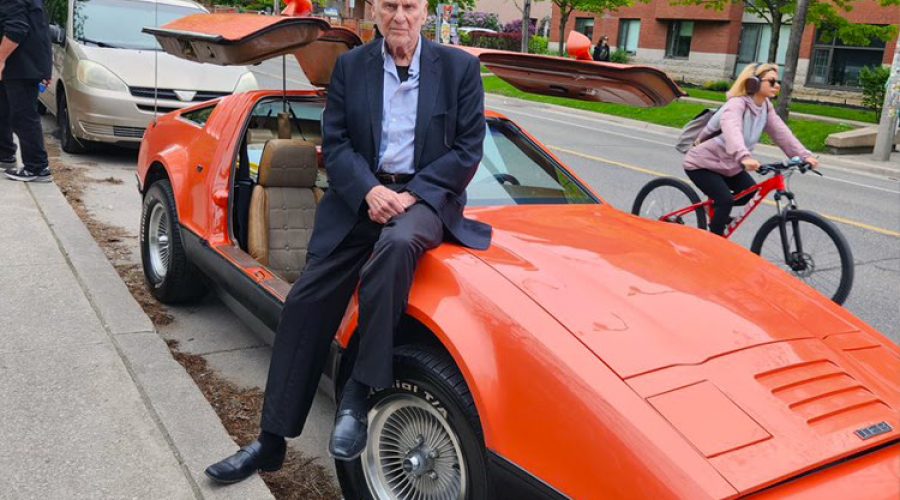

Fifty years ago a new car entered the North American market that was designed to be sexy, sporty and safe. The Bricklin SV1 was indeed all what it was marketed to be, including gull wings, but less than two years after its debut production stopped because of a lack of funds.

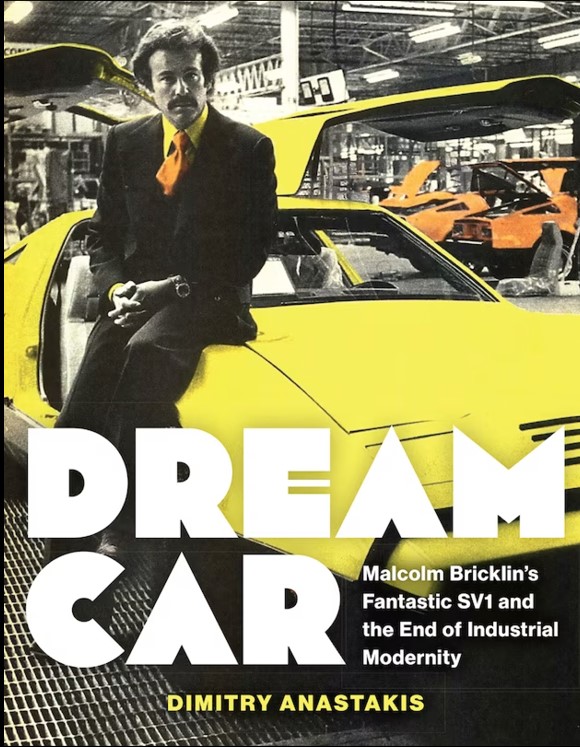

The story of the ill-fated car is captured in precise detail in the book Dream Car, Malcolm Bricklin’s Fantastic SV1 and the End of Industrial Modernity. The book is written by Dimitry Anastakis, who is the L.R. Wilson/R.J. Currie Chair in Canadian Business History in the Department of History at the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto. He is a historian, who is also a student of cars and teaches a course in it as part of his curriculum.

Anastakis began the book in 2007 and over the course of the next 17 years he completed it. His book is not the first about the Bricklin, which had a song written and sung by Canadian Charlie Russell in 1975 to pay homage to it, and two documentary films. I have not read the other books or seen the docx, though I did find the song interesting and amusing.

I am confident in saying that there is no comparison in either literature, cinema or song that has nearly the same amount of detail that Anastakis put into his project. His book reads like it was written by a historian with plenty of citations. The bibliography is 23 pages and done in small type otherwise it would be longer. In total the book is 478 pages. Anastakis said he titled the book Dream Car because from its very beginning and throughout its brief yet fantastical existence and in the decades after the car and its company had failed, the idea of the Bricklin was regularly portrayed and seen as dream. Anastakis writes “almost anyone who was part of this venture or opined on the Bricklin invariably came to connect the SV1 to the idea of a dream, either as a potentially magical success or as a nightmare of folly and waste.”

The book is combination of a portrait of the car, the automotive industry and, in particular, a biography of the two people who were involved in the construction of the Bricklin and its financing. Malcolm Bricklin, whom Anastakis interviewed for the book and who attended its book launch earlier this year, and the late Richard (Disco Dick) Hatfield, the onetime Premier of New Brunswick, collaborated to make the Bricklin a reality. Bricklin, an American who helped bring Subaru to America in 1968, was the Elon Musk of his time, which is to say a disruptor in the car manufacturing business. Anastakis describes Bricklin as an automobile entrepreneur archetype, “the quintessence, the homo erectus, (Latin for up-right human) of the species.” Anastakis also uses words like promoter and innovator to describe Bricklin, someone who seemed to have “all the necessary chutzpah” to bring a new car to the market since the 1940s. He also uses words such as “innovator, showman, cowboy, playboy, dealmaker and survivor.” The native of Philadelphia was the epitome of pursuing the American dream with a vehicle that dripped with features to appeal to a market looking for something new. Selling the vehicle as an object of sexual desire figured prominently into the ethos of the launch. Hatfield became the perfect partner, the Premier of New Brunswick trying to make his province a major player in Canada. As Anastakis writes, New Brunswick was Canada’s “least economically advanced province.” Anastakis says Hatfield was the “politician, performer, industrial proselytizer, dream-weaver, collector, bachelor statesman, drug user and survivor.” Anastakis says all Hatfield had to do was “convince his fellow New Brunswickers that his dream and Malcolm Bricklin’s dream was their dream, too.” Anastakis adds Hatfield was looking to spark his province and the Bricklin could be a “dramatic showcase for the province’s innovative potential.”

Collectively he says Bricklin and Hatfield were “dissimilar yet sharing many traits…forever famously entwined in each other’s legacies. In the end, they were both promoters and salesmen, one ultimately successful by every measure of the American dream; the other, not so much, try though he did.”

A big part of the realization of the Bricklin was the auto pact signed by Canadian Premier Lester B. Pearson and U.S. President Lyndon Johnson in 1965. It allowed the Big Three U.S.-based auto companies to send cars and parts across the U.S.-Canada border without paying tariffs and fully integrate their Canadian facilities into their U.S. operations. So this meant The Big Three could use their Canadian facilities to build for the entire North American market instead of only Canada, thus making all their operations even more efficient on a continental basis. When you think about all the saber rattling Donald Trump is doing now about slapping tariffs on the Canadian automotive industry in advance of taking office in January, that auto pact was huge – or “yuge” to use an often-mocked Trumpian word.

The first Bricklin was built in just a few months and featured four futuristic elements that separated it from anything of its kind – sleek shape and profile with pop-up car lights, gull-wing doors, plastic skin and innovative safety features. But the cost of producing the vehicles was too much and, ultimately, that led to the end of manufacturing. Almost 3,000 were built and today, there are about 1,500 still in existence and a club specifically devoted to the car.

Anastakis has an assortment of songs sprinkled throughout chapters of Dream Car because music and automobiles have always been intertwined. He writes, “car music provides the soundtrack of modernity.”

I enjoyed reading the book and Anastakis’ musical taste.

The book is available for purchase on Amazon.

Perry Lefko is the Content Manager of The Car Magazine. He can be reached at [email protected]. Feel free to forward any story suggestions or comments.